A different kind of father

Love and death are inextricable. If you don’t love you won’t notice death. The first death to have a considerable effect on me is that of my father-in-law, Tom Saunders.

Tom is one of the most delightful human beings I ever meet. He’s ex-RAF. He taught the King of Jordan to fly. He was also part of the Meteor Aerobatic Team – a precursor to the Red Arrows – and there are numerous photographs in our house of him flying with them. In most of these photos his aeroplane is upside down. And if you look carefully with a magnifying glass you can just about make out his face and see that he is grinning.

When he left the RAF he joined British Aerospace and constantly jetted around the world selling commercial airliners. The family joke is that this was cover for his real job as a spy. His work involved selling to the national airlines of various countries, so I’m sure he formed relationships with many government ministers around the world, and being an ex-serviceman I’m equally sure he was ‘debriefed’ whenever he returned home – a sort of ‘soft’ intelligence-gathering operation.

But we prefer to think of him as a proper spy. He always delighted in telling stories of flashing his American Express card or Marriott Hotel key card to gain entry into various government buildings around the world, of bringing back huge tins of caviar from Iran, or eating monkey brains to keep in with some foreign potentate.

At home he was equally eccentric: he had an enormous jar which contained the ‘toys’ from every Christmas cracker that had ever been opened in the house, and he was famous for cooking eggs in the kettle when Jane, my mother-in-law, was away – more than one of which exploded, leaving the tea permanently tainted with a slight flavour of scrambled egg.

He was very much anti snobbery and had a particular dislike for ex-servicemen using their rank after they’d left the service. A local neighbour made an annual visit for Christmas drinks, and when he appeared at the door Tom would welcome him in and shout to the rest of the house: ‘Everybody – the Commander is here! Commander Crill! You must come and welcome the Commander.’

He was always so positive towards me and what I did in a way that my own father found impossible.

‘What are you up to?’ he would ask.

‘I’m doing a voice over for the Peperami sausage on Tuesday, then at the end of the week I’m shooting a pop video for Zodiac Mindwarp and the Love Reaction. And then Rik and I have had an idea for a sitcom about two losers living in a flat in Hammersmith.’

‘How absolutely splendid. You are a clever chap. That’s marvellous. Well done.’

The way it comes across on the written page makes it sound fake or affected, but he was always very genuine. I like to imagine that he used this positivity to inspire the men under his command in the RAF.

It’s a stark contrast to my own father, who would wince and say: ‘Will there be a lot of bad language in it?’

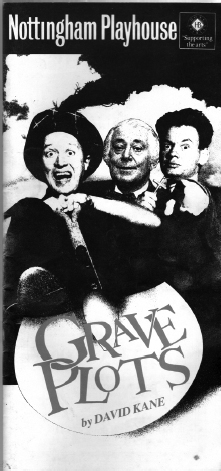

In 1992 I’m in a production of a play called Grave Plots at the Nottingham Playhouse. It is not the best thing I ever do. In fact it’s what you might call a flop. We play for three weeks and then it comes off and the hoped-for West End transfer never materializes. But my mum and dad come to see it and afterwards Dad says he’s pleased to see me in something ‘proper’ at last. By ‘proper’ he means a) a play with no swearing in it, and b) a show where the audience aren’t hyped up and hysterical, because he finds that uncomfortable and unseemly. He likes his theatre to be reverential. Culture is something to sit through patiently, and at its best should never be fully understood.

In 1993 when Rik and I are playing the Hammersmith Apollo with Bottom I look into the audience to see Tom laughing so hard that he is sliding off his chair onto the floor and I genuinely fear that he might be having a heart attack. Dad never comes to a Bottom show.

Why are you being so hard on your dad, he’s your dad!

But fatherhood is active, you have to constantly earn it, it’s not as simple as sharing a bloodline. There’s a very simplistic view of fatherhood promoted on today’s soaps – that the bond is automatic and cannot be messed with.

‘But he’s my son,’ some long-lost character will wail, as if biology trumps everything else.

I felt a lot happier in my own mind when I stopped expecting anything from my dad. Obviously it’s a deep scar, as this book testifies, but practising Stoicism I’ve learned to see it more objectively. Not with complete success, but with enough to let me live a happier life with fewer panic attacks and marginally better sleep.